|

You are all the proud parents of either pre-teens or teenagers and as you will all be aware this is a time of tremendous developmental change. As a psychologist I’m fascinated by this period of change and am curious about the reasons for these behaviours. As a parent I was probably as bewildered and confused as anyone about what was with my teenagers.

Understanding what’s underlying and driving some of these confusing behaviours can be helpful in developing useful parenting strategies. Developmentally adolescents are on the next stage in their journey towards becoming independent adults. Moving from being totally dependent on their parents as babies and toddlers towards developing the skills that will allow them to live independently. Teenagers are renowned for pursuing excitement, novelty, taking risks and preferring the company of their peers to parents and other mature adults. These traits can make them challenging to parent and war stories of difficult teenagers abound. Neuroscience has been able to tell us that adolescent brains have already reached 90% of their full size, so it’s not that teenagers are lacking in brain cells. However, during adolescence the brain does a tremendous amount of re organising which slowly progresses over the teen years and into the early 20s. The advantage of this re organisation is that brain processes become much speedier and more reliable, but this comes at a cost of some flexibility, we lose the ability to so easily add to our behavioural repertoire. If we consider language acquisition, we know that babies are born with the ability to learn any language they are consistently exposed to. As we grow and develop our understanding of our primary language/s it becomes more difficult to learn an additional language. We do become much speedier and more efficient at understanding our primary language, but it comes at the cost of flexibility to add new languages. These behaviours of seeking excitement, novelty and risk and preferring the company of peers are all symptoms/evidence of a much more flexible brain that serves the purpose of allowing teenagers to move into new and challenging situations in a way that many of us adults would hesitate to do. Hopefully with some more insight into why teenagers do what they do we can better choose parenting strategies that can support this transition into adulthood smoothly and with a little less conflict. Parental involvement that allows independence while providing the reassurance of connection is likely to be the most successful approach. Next post I’ll be talking more about specific parenting approaches that work well.

0 Comments

First step is to clarify what’s going on. Sometimes children are simply over tired or beginning to feel unwell. Think back to the past few days or weeks, has it been very busy or are there any signs that a cold or other is taking hold? Some early nights or a very quiet day at home may be the solution. If there is something else going on, ask your child to explain to you what their thoughts are. It may be helpful at this stage to email the class teacher to see if they have noticed anything different happening that is causing your child to feel reluctant about going to school. Some difficulties that seem to come up frequently are; conflicts with friends, a misunderstanding with a teacher, worries about school work, the journey to or from school or it could be a general worry or anxiety and the young person can’t say why they are worried exactly or it may be a few of the above concerns put together.

Next step is to discuss the reasons why school is important. Parents can use this as an opportunity to share family values about learning, social growth and development. You could talk about the opportunities to engage in sporting and cultural activities and the wide experiences schools offer for personal development in a huge range of directions. Of course, there is also a legal obligation in New Zealand for young people to attend school. This step is important and in behavioural psychology we would say that this is when we become very clear about what the expectation is for behaviour. Young people need to know that their parents expect that they will attend school every day. Now that everyone is clear about what the expectation is and the reasons for this and the reasons why this is difficult now, we can start to generate some solutions to the problem. A great place to start is to think about when aspects of happily going to school are happening already. Look for those times when school is eagerly anticipated or something great happened at school. Consider what was involved in that situation. What elements of that can be applied more broadly so that school can become something to enjoy rather than avoid. If you need more support than can be delivered here please contact [email protected] for further specific support. At times we will all be confronted with difficult social situations where someone is saying something we find challenging. This may be saying unkind or inappropriate things about a friend or acquaintance or may be statements contrary to our own beliefs. Many people find these situations awkward and uncomfortable. Young people are developing the skills to effectively manage these kinds of scenarios and may need some help to do this.

There are three commonly used but less useful/functional reactions to difficult social interactions, these are:

Better ways of managing difficult social interactions are: Consciously deciding that the incident is not worth your time or effort to deal with and to ignore it or walk away from it. The difference between this and being passive is that this is a considered decision rather than simply allowing someone to do something to you. Another option is to choose to act assertively. Whilst this can be difficult to do at times it may be the best choice. Acting assertively means to state your needs/thoughts in a calm, non-threatening way. Young people may need help to think through these options and it may be helpful to practice in advance, so you are more confident of saying what you want to say. People who may be able to help with this are class teachers, counsellors, school deans, parents or more socially confident peers. One aspect of bullying in schools is the impact of bystanders. Given how busy and well populated most schools are it is often the case that bullying incidents take place in front of witnesses or bystanders.

What is really important for parents and educators to understand is that there is a well known phenomenon in social psychology called bystander effect. Essentially this is the typical human response or non response to an individual in trouble. If you are interested in the history of this check this link, https://psychology.iresearchnet.com/social-psychology/prosocial-behavior/bystander-effect/ which is a summary of the history of this phenomenon. Typically, what the researchers found is that as soon as there is more than one person witnessing a problematic situation they are less likely to respond to it than if it was just one individual witnessing the event. While the research confirms that it is very difficult to overcome this response in the general public, there is some evidence that children can learn to manage this impulse better if they are given some support. There are three main strategies recommended.

So as parents how can you use this information to support your child. Take some time at your next family dinner or on a car ride to tell your children what you expect them to do if they see someone being bullied. It’s really important to talk about likely scenarios so that they know how to act without putting themselves at risk. Responses may range from quickly finding an adult, to telling a peer that it’s not OK to do what they are doing at the time of the event. When opportunities arise for us as parents to demonstrate what we would like our children to do ensure you take them and then explain to our children why and what the hoped for impact was. If you haven’t had the opportunity to do this you can always set up a practice session. Ask your child to tell you about what they may consider a typical situation and then have them practice with you what they might do. Of key importance is that adults only demonstrate the undesirable behaviour. We don't want our kids practicing what not to do! Sounds awkward I know but there is plenty of research evidence that shows that practicing a behaviour leads to children doing the behaviour when the situation arises in real life. The final point, environmental cues is perhaps more directly suited to schools but at home this can also apply at home. Support school initiatives such as pink shirt day, show your children this article and talk about your expectations in terms of their behaviour. New Zealand has a problem with bullying behaviour but there are plenty of small and simple things we can do to change this. Bullying is a topic that has recently been in the news headlines. The Education Review Office published a study in May this year based on evidence gathered from 136 primary, secondary and composite schools in terms 1 and 2 in 2018. The results were sobering with high rates of bullying being reported.

It is key to have a clear and shared understanding of what we are calling bullying. The bullying free NZ website, defines bullying as having four clearly identifiable factors:

https://www.bullyingfree.nz/assets/Uploads/Tackling-Bullying-A-guide-for-parents-and-whanau.pdf If your child comes home from school and talks about either a bullying incident they have seen or themselves experienced the first action should always be to provide empathy and understanding. Once you have assured your child that their emotions and feelings are important and valid it’s helpful to clarify what the incident involved. Did the incident your child is talking about meet the definitions provided above? You could talk through each criterion and consider an alternative explanation if there is one. Young people are learning the skills of managing increasingly complex social interactions and it is easy for them to become unsure or confused about how to proceed. Being clear about the behaviours your child is experiencing at school is the best way to begin to create solutions for managing them. Eye contact can be a feature of social communication. Some people can find this very difficult. The following article suggests that just generally looking at the face of the person you are talking to is an ok substitution for eye contact. Read on for more information.

https://digest.bps.org.uk/2019/03/07/heres-a-simple-trick-for-anyone-who-finds-eye-contact-too-intense/ To finish up my series of blogs on anxiety I’ve created a list of tried and true resources for you and your child/young person.

As an educational psychologist, I've used a number of resources to support my work and these are a few that I am happy to recommend. Not every resource will work for every person. If you don’t find it helpful or your child doesn’t seem to benefit from it then try something else.

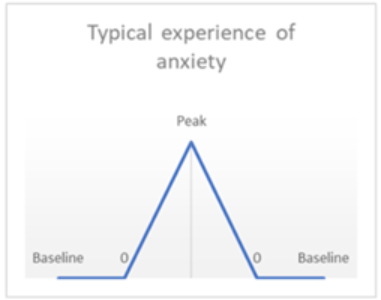

Let’s talk about anxiety. Today’s article will discuss the typical experience of anxiety, fear or worry that everyone encounters. If you are concerned that anxiety is more than every day, I have some further information at the end of this article. First up let’s get our minds into anxiety mode. Think about a near miss situation when you were driving a car. How did you feel during and immediately after this situation? Did you get back in your car the next day? Did anything change in your driving behaviour? Anxiety is something that our thinking mind creates which is reflected in our bodies. From an evolutionary perspective anxiety is a useful adaptation because it helped to keep us safe from sabre tooth tigers and other hazards in the environment. The anxiety helps us to consider, plan and strategize how to keep ourselves safe. In our modern world there are certainly things which anxiety legitimately helps us to negotiate safely. The picture above illustrates the typical pathway for anxious feelings. We start at a baseline of feeling confident and able to manage a situation without concern. Something triggers a rise in anxiety which will reach a natural peak and then begin to subside until we reach baseline again. Problems commonly occur when we interrupt the process of:

When should parents seek professional help for anxiety? · If your child’s worries/anxiety significantly interfere with the child or family daily functioning and routines. · The worries/anxiety are not age appropriate. · The worries/anxiety persist across an extended period (longer than 6 months). Questions to ask about your situation to help decide whether further support is needed. · Is anxiety stopping my child from doing the things they want or need to do? · Do most children of the same age also have the same fear or worry? · How severe is my child’s reaction? (sourced online from the Macquarie university centre for emotional health). Next month I’ll talk about some of the helpful things parents and teachers can do to support young people to manage anxiety. Psychology has a lovely, neat answer to that question. A powerful tool we can use to get our children to behave is to point out what they are doing right and to keep on pointing this out to them. Reinforcement is the technical name used by psychologists to describe a very effective method of increasing behaviour. There is even a magic ratio associated with this idea of reinforcement, 5:1. This ratio applies to all human behaviour not just children’s behaviour. It is necessary to deliver five reinforcing statement to one corrective. This means that if you tell someone to do something you will need to follow that up with five other reinforcing statements that increase their behaviour. In fact, this ratio has implications for research into successful marriages. In a 2003 paper, Is there a formula for marriage?, John Gottman and James Murray write about the 5:1 ratio being a way to identify a successful marriage. Looking for a way to get your spouse to do the dishes/put the rubbish out? The science tells us that reinforcing desired behaviour using a ratio of 1 telling them what to do followed by 5 incidents of reinforcement will get them onto it.

This idea of reinforcement is famous enough to have made it onto T.V. on The Big Bang Theory https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JA96Fba-WHk. Check out this link to a clip of Sheldon, ‘training’ Penny to perform particular behaviours. As funny as this is, it is a little unrealistic, this is T.V. after all. There are a few technical inaccuracies in the video. Let me know if you can spot them. When you are working with human behaviour it’s not a great idea to reinforce behaviour with food, especially with as much frequency as needed to get to the 5:1 ratio. Leonard’s outrage at Sheldon’s behaviour is pretty much how most of us would react to this kind of manipulation of someone’s behaviour. If you would like someone to do more of a particular behaviour, step one is to make sure they know how to do that behaviour. If you aren’t sure, then step two is to show them how to do it. Then give them some opportunities to practice with a more skilled person who can guide them through the behaviour. All through this process make sure you are using reinforcement at each step. To reinforce well you must be specific about what someone is doing well. An example of a narrative in a setting where a parent might be teaching their child to cut an apple might go like this. “Great work holding the knife in a safe grip - you are doing it just like I showed you”. “OK, now put the sharp point into the top of the apple, making sure you keep your fingers away from the blade”. “That’s excellent”. “You’ve put the knife exactly where I showed you”. Each statement has a component of describing the exact action taken and an element of praise linked with that. Add on comments to increase the reinforcement could be, “you did such great work cutting your own apple, I’m going to have to tell mum/grandad about how well you are managing”. Remember the goal is that 5:1 ratio. With your own child reinforcement can also be a hug, high five, arm around the shoulder or other non verbal methods of demonstrating your approval. Even pointing to their action, smiling and giving a thumbs up will work once you are sure they know what it is you are pointing to. Being a child means that there is a lot of stuff you don’t know. Most of the time as adults instruct children they mix in reinforcement. Children are then happy to accept the instructions and learn a new skill and complete set tasks. However, when something goes wrong and you start to wonder how you are going to get your child to do any one of the myriad things we ask of them in a day or week think about how you could add a little reinforcement into the mix and see if you can make a difference with just this one small change (in your behaviour). Psychologists can provide insights about how to teach children to manage their behaviour in ways that are socially acceptable. It’s a bit of a minefield to blog about this topic as there are so many questions that arise from even simple statements. As I wrote socially acceptable I suddenly thought, hmm, socially acceptable, to whom?

OK, so let’s define what I mean by socially acceptable. I mean socially acceptable for whatever environment we are in. The photo in this blog of a pinata is a perfect example of this. There are few times when it's socially OK to hit an object with a stick until it breaks. At a party with a pinata it's just fine. If the environment is home, relaxing and watching TV, socially acceptable could mean lying on the couch or on the floor, eating popcorn using hands from a shared bowl, not talking much to anyone else aside from possible one or two word utterances or laughter. If the environment is a special occasion visit to a fancy restaurant, to celebrate mum and dad’s wedding anniversary, very few of the previous behaviours would be considered socially acceptable. What is likely to be socially acceptable is sitting upright on a chair at a table, making eye contact with other people at the table, using a fork and knife and eating only from your own plate, unless explicitly invited to share, responding to questions in sentences and initiating some conversation with the other people at the table. So, who defines what is socially acceptable? The answer to that is the society in which we live. Our family background, culture, the country we were raised in, and or live in all contribute to this sense of what is socially acceptable. If we look into the distant past of human history there hasn’t been much that has never been considered socially acceptable at one time or another, up to and including eating other people! If your child is doing something that has been termed socially unacceptable you can quietly think to yourself that it’s likely that at some time in the past, in a different environment or in some other culture this behaviour has been completely socially acceptable and it’s really just a socially defined construct! While (hopefully) this thinking might make us feel a bit better about what our child has just done, it doesn’t take us any way toward changing the behaviour in order to make things go better for our child. It does help us to understand where things might start to go wrong for a child. Children are still learning about what is and isn’t socially acceptable. It’s a huge learning task for a child as the ground rules keep changing depending on the environment. In addition to this, children are also growing and developing physically so that they are also learning what is socially acceptable for someone of their age. What is OK for a child of two is at times not OK for a child of five. The question remains, what do we do when our child behaves in a way that is considered socially unacceptable. Prevention is always better than cure. One way to support children and young people is to explain to them in advance what might be expected in a social situation. It’s always good to do this in a casual way so that you minimise any pressure. Driving in the car is a great place to have these conversations. Another is while you are doing something together, or just in the same place together. My kids used to congregate in the kitchen while I was cooking or sorting stuff out from the work and school day. Just casually drop into the conversation that some new situation is coming up. Ensure that you talk about the new experience in positive terms and describe what might happen. It’s good to talk about variations in the general rule. These are the moments where things can go wrong for a child who is learning about a new situation. Consider teaching a child about a formal dining experience. You may tell your children they will need to stay sitting at the table until everyone is finished eating. You might want to also explain that there will be a few reasons that you might need to get up. Going to the toilet is one. Explain to your children how they might politely excuse themselves from the table. Give your children a chance to come up with their own ideas about how they might manage the situation. At times it can be fun and useful to take time to practice the new skills. Perhaps the children are meeting some new adults at a parent’s workplace, and you think it’s likely someone might offer to shake their hands. It’s a good idea to have a practice first. Give your children lots of praise and positive feedback as they provide their ideas and practice the new skills. Keep this up as they try the new experience and even after they have finished the new experience. If something doesn’t go according to plan reassure your child that they did their best and are learning these new skills. The next time they try it’s likely that things will go better. |

AuthorRobyn Stead, Child Psychologist and Educator, lives and works in central Auckland. Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed